LatamPolitik: In Argentina, All That Glimmers Isn’t Silver

This week, Argentina held the first meeting of the Federal Hidrovía Council, a body created late last year to modernize a segment of the Paraná-Paraguay waterway that includes part of the Río de la Plata. We know what you’re thinking: A government body had a meeting about a river – who cares? But we’re not talking about just any river. We’re talking about one of the most important if overlooked rivers in the world, the changes to which have profound regional and global implications.

The first rule of geopolitics: Rivers are important. Most of the world’s great civilizations, powers, and cities owe their existence to the rivers upon which they are founded. The Sumerians had the Tigris and Euphrates; China has the Yellow and Yangtze; Rome had the Tiber; Britain has the Thames; the United States has the Mississippi.

The Río de la Plata rivals them all. It is the widest river in the world at roughly 220 kilometers, and far more important, it’s where the Uruguay and the Paraná rivers meet. A ship entering the Río de la Plata from the Atlantic Ocean can go almost anywhere worth going in the Southern Cone, after passing Buenos Aires and Montevideo, of course.

The river’s name, like much of Latin America’s history, is based on colonial fiction. The Venetian explorer Sebastian Cabot got some silver objects from the Guaraní in the early 1500s, so naturally he assumed he was near the mythical Sierra de la Plata, or Silver Mountains. (The name “Argentina” is derived from the Latin word for silver, “argentum.”) No one ever found Cabot’s Silver Mountains, but European explorers found plenty of other resources to exploit. The Río de la Plata was their ticket in.

The conquistadors are gone, but the Río de la Plata still connects this fertile part of Latin America with the rest of the world. Some 70 percent of Argentine exports and more than 100 million tons in local cargo and shipments from Brazil, Bolivia, Uruguay and Paraguay pass through its waters. Today, the Sierra de la Plata has become the Sierra de la soybeans, corn, beef, lithium, and countless important exports upon which the world is increasingly more dependent on Latin America for. It’s little wonder that any potential change to what happens on the Río de la Plata or network generates intense controversy inside and outside the country.

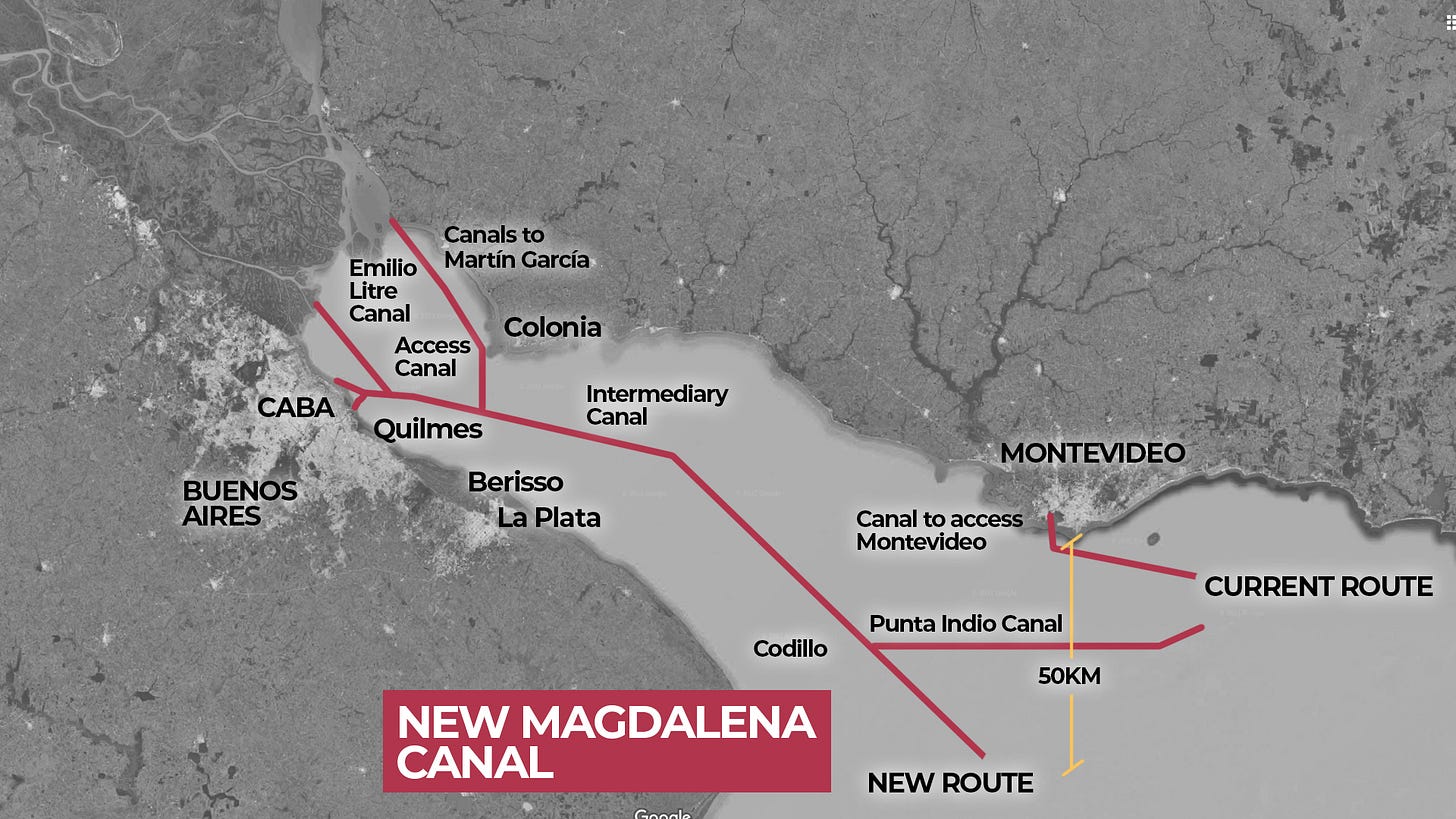

Crucially, the Argentine government’s plan is not simply to modernize the Paraná-Paraguay waterway, but to fold an even more geopolitically important project into the overall plan: the Magdalena Canal. Because of the various depths in the Río de la Plata, the Canal Punta Indio is currently the only access road to the entire La Plata basin, and that means any ship entering or exiting the Río de la Plata must also pass through the Canal de Acceso Montevideo. The Magdalena Canal would change all that…and might also silence critics of the Federal Hidrovía Council, who hoped for outright nationalization of the concessions currently up for grabs on the Paraná-Paraguay waterway.

“The Magdalena Canal.” Source: La Nacion.”

Argentina has been talking about a project like this for decades. But the current government means business, having already called for a tender to dredge the new canal and dedicating $25.8 billion Argentine pesos (about $280 million) for the project. It would enable Argentina to benefit from the services and jobs that Uruguay currently enjoys in its stewardship of the Canal Punta Indio, and it would allow Argentina to bypass Uruguay entirely. In the words of Argentine Interior Minister, Wado de Pedro, the Magdalena Canal “is one more step towards the strengthening of our national sovereignty.”

It seems that Argentina — a country that has been punching below its geopolitical weight for centuries — is behaving like a country that wants to cash in on the immense advantages afforded by its geographic position. But it raises a lot of important questions. Will Argentina nationalize the canal or rely on private companies? Will the projects even be completed? If China wins one of the tenders, what will the U.S. do, and what will it mean for Argentine foreign policy in general? How will other countries, especially Uruguay, react to Argentina’s moves towards securing its sovereignty after all this time? Stay tuned for more. This story has only just begun.

Extra! Extra!

The EU ambassador to Venezuela was declared persona non grata after the EU passed sanctions against 19 Venezuelan officials.

Japan agreed to help Honduras rebuild the Guacirope bridge and to donate heavy equipment to help Honduras recover from hurricanes Eta and Iota.

Soybean oil prices in Argentina hit multi-year highs thanks to tight supplies from the U.S., a delayed Brazilian harvest, tight volumes of sunflower oil in Ukraine, and record high canola futures for Canadian canola.